In his will, written in 1801, Robert Richard Randall gave all of his property to a charitable trust known as the Trustees of the Sailors’ Snug Harbor in the City of New York for the creation of a retirement home to be known as “The Sailors’ Snug Harbor.” Alexander Hamilton and his assistant, Daniel D. Tompkins, drafted the will. The facility opened on Staten Island in 1831 and is one of the first retirement homes established in the United States and the site of its first five National Historic Landmarks. The Trustees received court approval to move the home from Staten Island to North Carolina in 1976 and sold the site to the City of New York. The City then began the process of adapting it for modern use.

The museum moved from Noble's home, where it was established, to Building D, a derelict landmark at Snug Harbor Cultural Center in 1992. Its goal was to answer a long-heard cry from the community to address and preserve the history of Sailors' Snug Harbor. John A. Noble was passionately involved in the fight to save the home from the wrecking ball from the time in the late 1940s when the Sailors' Snug Harbor Trustees, in an attempt to reduce costs vis-à-vis the decline in residents, began demolishing some of the historic buildings.

Inspired by Noble's passion for mariners and their venerable home, the Noble Maritime Collection undertook the $3.2 million adaptive reuse of Building D, a former dormitory, and one of the famous "front five" buildings on site. The building was designed by Minard Lafever in the Greek Revival style, constructed in 1840, and occupied as a dormitory in 1844.

The Sailors' Snug Harbor was one of the first democratic, non-discriminatory charitable institutions in this country. The sole requirement for residency was five years of maritime service under the United States flag. There were no admission requirements regarding age, religion, nationality, physical condition, sex, or age, and Sailors' Snug Harbor, where each resident was called "Captain," became a democratic melting pot of people from across the globe cared for by hundreds of employees largely from Staten Island. A self-contained community, the site's farm produced its food and tobacco. The Trustees built a large hospital and a tuberculosis sanatorium, and although both structures have been demolished, their capacity demonstrates the scope of the Harbor's offerings and its world-wide reputation.

Robert Richard Randall was a wealthy entrepreneur, and his will provided for the creation of the retirement home at his farm in Manhattan, in the area of what is now Greenwich Village. Like the rest of Manhattan, it rapidly increased in value. The Trustees determined that it would be more prudent to use the Manhattan real estate as a source of funding for the Sailors' Snug Harbor and, with court approval, situated the facility on a farm on Staten Island, then a favored summer retreat. It consisted of north shore footage overlooking the Upper Bay, the Kill van Kull, and Manhattan in the distance. Meanwhile they built about 250 residences on the Manhattan property. From Astor Place to Tenth Street, the streets became lined with elegant homes in the Federal and Greek Revival styles, and their rental provided income to maintain the mariner's home, which opened on Staten Island in 1831.

The Trustees were able to construct buildings as needed, and in 1827 they advertised for the first, a brick or stone building to accommodate 200 seamen. Minard Lafever, a 33-year-old upstate carpenter, submitted the winning design. The Trust used its extensive resources to make the site comfortable and to furnish and decorate the buildings; it became one of the most lavish nursing homes in the world. Over the years 55 buildings, including a replica of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, a 30-room residence for the Harbor's Governor, a private morgue, powerhouse, chapel, music hall, hospital, greenhouse, and dairy farm were added to the site. With its St. Gaudens statue of Randall, Neptune Fountain, Victorian gazebo, stands of pine trees, walks lined with chestnut trees, flower gardens, ponds, and cemetery dubbed "Monkey Hill" by residents, the Harbor was, as John A. Noble wrote, "a truly baronial estate encompassing great lawns—woodlands—lake and stream—secret nooks, and many a strange and interesting vista or object."

The facility grew quickly, as men across the globe heard about it and sought refuge there. By the early 1870s, it housed over 350 people in several buildings. As the population grew, so did the staff and the amenities the site offered. Eighteen-foot, carved Roman doors adorn the Music Hall. The "front five" look like Greek temples. The Neptune Fountain spouts its waterworks elegantly. The stately features more than anything reflect the kind of care that Sailors' Snug Harbor gave to those who found it, and the respect for the simple, worn sailors who helped make the United States of America the great commercial and maritime power it is today.

Sailors' Snug Harbor's wealth stands in sharp contrast to the social and financial situation of the average mariner. Most were destitute; many could not speak English and were handicapped or ill. They had survived passages on leaking vessels and endured storms, shipwrecks, sea battles, hunger, and illness aboard them.

As J. Ross Brown notes in his classic Etchings of a Whaling Voyage, "… the sailor…is pictured in books as leading a highly colored life, with a wife in every port, and as being a 'jolly tar.' It is to be feared he never was that. His life was hard, dangerous, and ill rewarded. He belonged, and still serves as one of the classes that must give up much in his life for others; must endure absences, curtailment of acquaintances, and loss of opportunity such as landsman enjoys. Pent up on shipboard his confined impulses explode when he reaches the shore. He must spend and splurge. This keeps him in serfdom. That he can see strange lands is another delusion; the most he usually perceives is through a porthole or over a taff-rail. Thus it is that seamen get little out of life while performing the greatest of services to their fellows."

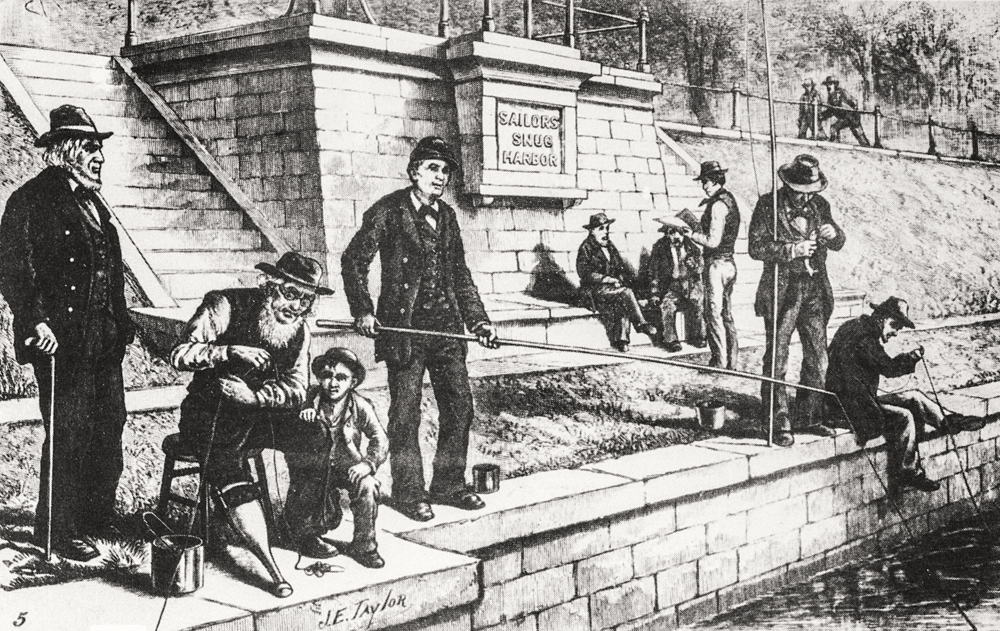

When Robert Richard Randall died in 1801, a young boy of 12 or 14 who went to sea might never return home. As Brown notes, without any savings, "worn out" and "decrepit" after years under sail enduring unimaginable hardships, a sailor would find himself homeless and his fate—dying penniless and alone—fixed. To him, Sailors' Snug Harbor was a dream come true. There he could find refuge, and be fed, clothed, and treated for illness or injury in an atmosphere of respect. Men were forbidden to drink on site, but they had the freedom to come and go. For spending money, they could sell their handicrafts, things like hand-woven baskets and ship models. There was camaraderie, entertainment in the Music Hall and popular amenities—from ham radios in the recreation hall to fishing on the pond As Noble wrote; Sailors' Snug Harbor was "a home and a club, a ducal estate, for a distinguished breed of man."

The Noble Maritime Collection maintains a collection of artifacts and documents gathered in the 20 years since the museum came to the Snug Harbor site and interprets the site’s history in its exhibitions, programs, and publications. In 2010, the Trustees made the Noble Maritime Collection the custodian of its prestigious collection of art and artifacts in order to catalogue, preserve, and exhibit the Trust’s collection.

©2013 The Noble Maritime Collection all rights resrved